Should You Use Ozempic?

Everyone is soon going to know people doing these drugs

This is not the typical column on Culturcidal for three reasons.

The first is that it centers on a health-related issue. More specifically, on a new, wildly popular drug – one that I’m not even taking. Second, this column borrows heavily from an outstanding new book by Johann Hari called, “Magic Pill: The Extraordinary Benefits and Disturbing Risks of the New Weight-Loss Drugs.” Third, there is no ultimate conclusion. This is a drug with an enormous upside along with some scary downsides and a truly staggering number of unknowns.

So, why write this at all? Because this drug and similar ones have the potential to be, no exaggeration, one of the most significant inventions of the last fifty years.

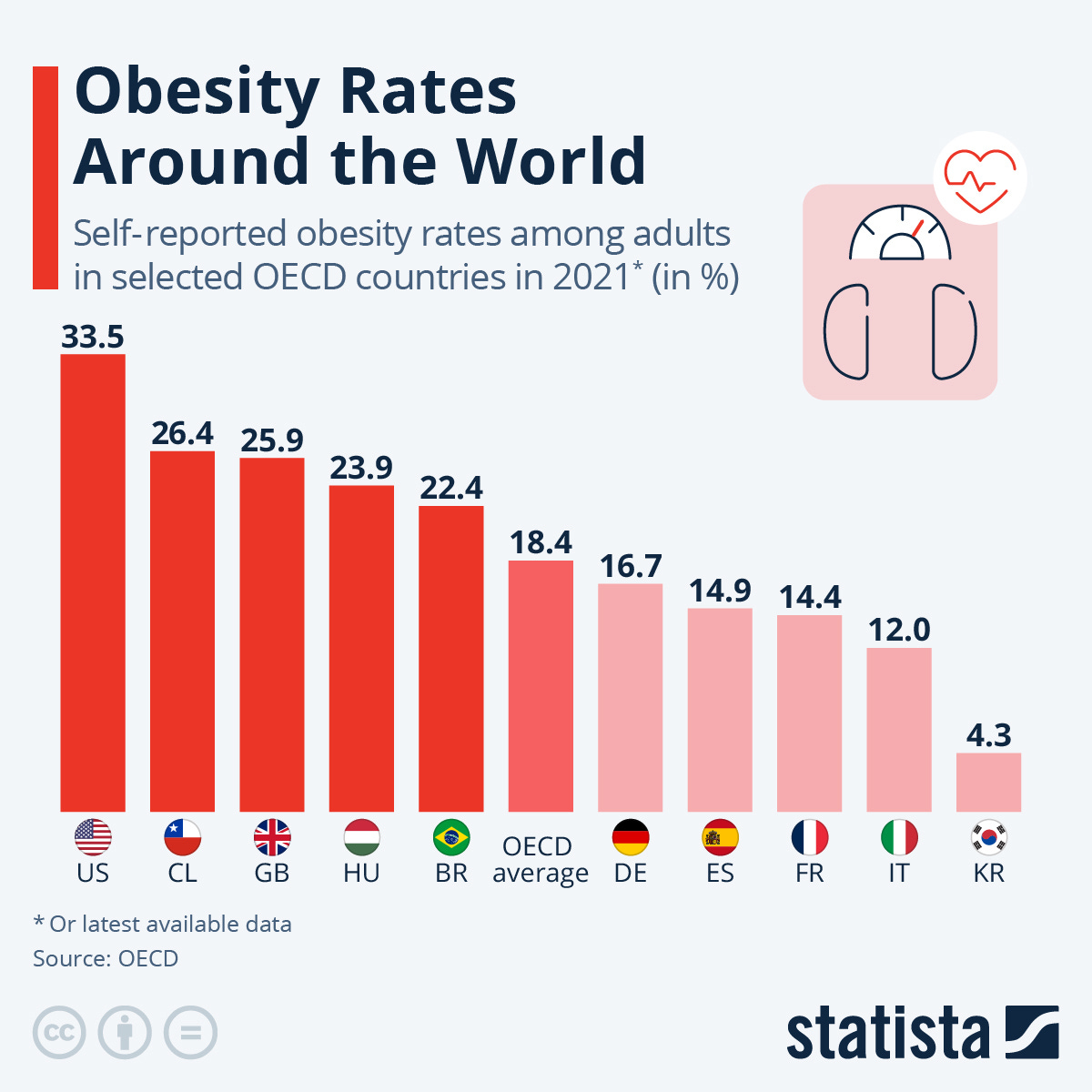

That’s because, contrary to what the fat positivity wackos will tell you, obesity creates huge health risks and we live in a world where it’s already out of control in a lot of nations

Three things make this even worse than it appears at first glance. First, the onset of this has been very rapid. As Johann Hari notes in the book:

But according to scientists at the National Institutes of Health in the United States, this began to change in the late 1970s. Obesity had likely been rising very slowly since the turn of the twentieth century, but suddenly, it went supersonic. Between the year I was born and the year I turned twenty-one, obesity more than doubled in the United States, from 15 percent to 30.9 percent. The rate of severe obesity took a particularly disturbing turn: between my twenty-first birthday and my forty-first, it almost doubled. The average American adult weighs twenty-three pounds more than in 1960, and more than 70 percent of all Americans are either overweight or obese. England has followed a similar trend. In 1980, 6 percent of men were obese. By 2018, it was 27 percent. As a result, the World Health Organization says that obesity has nearly tripled globally since 1975. This has never happened before in the 300,000-year history of our species.

Second, pre-Ozempic, this trend was clearly looking as if it was going to get worse, not stabilize or decrease.

Last but not least – and I’m going to piss some people off here – there is no obvious solution. I can already hear people shouting through the screen, “Eat less and move more! It has to work! It’s physics! Besides, studies show it works!” Yes, it is and yes, they do. Short-term. There are many diets that work in the short-term for all sorts of people, but the unfortunate truth is that none of these diets work long-term for more than a tiny percentage of people. Again, from the book:

But scientists who investigate how diets work over the longer term have persistently bumped into something odd. ...Traci Mann is a professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota who has carried out some of the most detailed long-term analyses of the effects of diets… She could find only twenty-one studies that had followed dieters rigorously for two years, or, in a few cases, five years. So what did they discover? It turned out that two years after starting a diet and making a real effort to stick at it, you will— on average— weigh two pounds less than you did at the start. It’s almost nothing. This means the vast majority of diets fail. Traci was baffled. “It was like up is down, left is right, dogs were cats,” she told me. “Everything I read was the exact opposite of everything I’d been told my whole life. It was showing diets don’t work.” She has now been researching dieting for more than twenty years, and she keeps finding similar outcomes. “It seems that they work for the initial weight loss, and then back on it comes.”

We could get the best experts in the field and spend 50,000 words discussing why this is and at the end of the day, we’d have lots of excellent theories, but no definitive answers. This is just how it is.

However, this is also why there’s such a staggering market for drugs like Ozempic.

Ozempic works. People who take the drug lose weight. Sometimes large amounts of weight. In fact, a friend recently told me one of his relatives lost 100 pounds on Ozempic.

For a lot of people who have struggled with their weight, that’s all they really need to know because they know what being fat is like. It’s unattractive. It limits what you can do physically. It’s bad for your health. People really do generally think less of you for being overweight. Because of that, they may have tried dozens of diets, gone to trainers, gotten dieticians and it’s highly likely that they’re heavier than when they started all that. Meanwhile, everyone is pointing the finger at them, telling them that being overweight is some kind of personal failure.

Know what seems to solve all those problems? Ozempic. Because when you get on it, it replicates a hormone in your body called GLP-1 and one of the things it does is make you feel full, partially by making food move more slowly through your stomach. You’re basically going to spend all your time feeling as if you just finished overstuffing yourself at Grandma’s on Thanksgiving and you won’t WANT to eat. This isn’t the case for everyone, but when you do eat, you may get a lot less enjoyment out of the food. You won’t need any willpower, you won’t have to eat any healthy foods you don’t like, but you will lose weight. In fact, if you stay on it long enough, you will probably be skinny. Sure, you do have to pay for it, and you do have to give yourself a stick in the stomach each week, but it’s a small needle and it’s not all that painful.

So, if you’re overweight and you can afford it, you should get on this stuff, right? It’s a simple decision, right?

Actually, no. It’s not a simple decision at all. It’s quite complicated for a variety of reasons.

The first is that it’s almost shocking how little we know about this drug. Granted, we do know that diabetics have used these drugs for around 15 years while the FDA approved Ozempic for weight loss in 2021. That gives us an enormous amount of real-world data, which is incredibly important to consumers when evaluating the safety of a drug.

The flip side of that is they don’t know EXACTLY how the drugs are causing weight loss. Yes, it makes you not hungry, but HOW is it making you not hungry? Is it keeping your brain from maintaining a weight set point? Is it acting on your brain’s reward centers and making everything less pleasurable? Is it ramping up your brain’s aversion to unhealthy activities? Is it changing how your brain works in some other way? Whatever impact it’s having on your brain, will it be reversed if you get off Ozempic? Especially if you use it long-term? The unfortunate answer to that question seems to be, “Nobody knows for sure.”

Also, speaking of using Ozempic “long-term,” what happens AFTER you stop taking Ozempic? Per the book, you’re probably going to gain the weight you lost back:

Several clinical trials also investigated something else that would be hugely significant for people who wanted to use the drug. What happens to you when you stop taking it? It turns out that after they quit, most people regain two-thirds of the weight they have lost within a year.

This could be reminiscent of another drug that was once considered a “miracle” for weight loss: amphetamines. They did work for weight loss, but if people stopped using them, they gained the weight back. That turned out to be a problem because they also needed ever larger doses of amphetamines to get the same effect and the higher the dose, the more potential health problems it caused.

So, if you have to take Ozempic long-term, could something similar happen? No one really knows for sure. There really aren’t long-term studies on the impact of Ozempic, which is a little scary given that by some estimates, as many as 20-30% of the population might end up on the drug or something similar over the next few years.

We also can’t forget some of the rare, but terrifying potential side effects of Ozempic. As much as a 75% increase in the risk of getting thyroid cancer. Severe, extraordinarily painful pancreatitis and perhaps most frightening, gastroparesis. From the book:

The same group of Canadian scientists found that these new weight-loss drugs increase the odds of stomach paralysis by 3.67 times. Similarly, the risk of developing a bowel obstruction goes up by 4.22 times. A forty-four-year-old woman from Louisiana is suing both Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, claiming that she was insufficiently warned about this risk and that after taking Ozempic and then Mounjaro, she suffered a paralyzed stomach, and the condition made her vomit so violently that she lost teeth. Her lawyers say they are investigating four hundred other potential cases like this. Another woman named Brea Hand (who isn’t involved in the court case) told CBS News that when she developed stomach paralysis while taking Ozempic “the stomach pain was just unbearable, and I couldn’t keep anything down. I would drink something and within minutes, like five, ten minutes later, I would be throwing up.” The companies involved are disputing these legal cases vigorously.

Incidentally, from the stories I’ve seen about this in the news, gastroparesis appears to be a long-term problem, not something that just goes away after you stop taking the drug. It can cause malnutrition, starvation and lead to a generally miserable life.

There’s another significant side-effect that’s more controversial. That being, large amounts of muscle loss. The reason that’s controversial is twofold. First off, it’s standard to lose some muscle when you lose weight. The more fat you lose, the more muscle you’re likely to lose as well. So, it’s possible that’s all that’s happening. Second, the standard American diet tends to be overly heavy with fat and carbs already. So, if you keep eating the same crap, but eat much less of it, it’s quite likely you’re not going to get enough protein. That can lead to muscle loss, weakness, possible bone breaks, etc. My assumption has always been that if people diligently worked out and ate protein, they could avoid this, but I’m not so sure about that anymore.

There’s a woman I know tangentially who has always been in extremely good physical shape. Lean, muscular for a woman, fitness conscious, a health nut. Obviously very dialed in with her work outs and what she’s eating. Well, a friend and I were talking about her recently wondering what had happened. She lost a good bit of weight, lost a lot of muscle tone, and generally looked a little unhealthy. We didn’t know her well enough to ask, but we assumed she was sick and hoped she would get well soon. Well, a mutual friend who knows her better told me recently that she was on a sister drug to Ozempic and that’s why she lost all the weight. Why did someone like that get on Ozempic in the first place? That’s hard to say for sure, but it’s not hard to wonder if it was a big mistake.

At the end of the day, it’s still very difficult to tell people whether they should get on Ozempic or not just because there are so many unknowns, but because, as Thomas Sowell said:

There are a lot of question marks when it comes to Ozempic and how it may impact your health long-term, but we know that being obese is incredibly bad for your health long-term. Are the risks of being on Ozempic worse than the risk of being obese over the long haul? To the best of our knowledge, no, but since there’s so much we don’t know, that could change. In fact, that’s exactly what ended up happening in the nineties with another “miracle” weight loss drug, Phen-fen:

The author of the book that we’ve been quoting throughout this whole article wasn’t quite sure whether to recommend drugs like Ozempic to people and he split the baby this way:

But after thinking about this a lot, I have tentatively concluded that, for me, the benefits outweigh the risks, and for that reason, I’m going to carry on taking these drugs for the foreseeable future. The advice I started to offer other people was: if your BMI is lower than 27, you definitely shouldn’t take these drugs. If your BMI is higher than 35, you don’t have a family history of thyroid cancer, and you’re not trying to get pregnant, you should probably take these drugs. If your BMI is between 27 and 35, it’s more of a finely balanced debate. But I am also conscious that lots of reasonable people will look at the same facts I have looked at and reach different conclusions on this.

While that’s not unreasonable advice, there is one very obvious flaw with it. That is, since you are highly likely to regain the weight you lose on Ozempic and other similar drugs if you stop taking them, you’re going to have to continue taking them even after your Body Mass Index drops to a much more reasonable level.

In other words, once you’re in, you may be in for the rest of your life unless you want to gain the weight back. Is that a good trade-off? The honest answer is that no one on earth truly knows the answer to that question right now, but you have to suspect that somehow, some way, the answer is, “no.” That being said, I don’t know what to tell you on this either beyond, “Data is your friend. Let as many other people be guinea pigs for this as possible before you seriously consider doing it.”

I am officially obese and have been since more or less forever. I am also mildly diabetic and have been on insulin (10 units of Levemir a day) for about a decade. I lost a tremendous amount of weight--around 75 pounds--seven years ago as a result of a two-week hospital stay. Toward the end I was joking with the docs that I was going to write a book called "The Alexandria INOVA Diet: How I Lost 75 Pounds Lying Flat On My Back." I've kept that weight off owing in part to taking 60mg of Torsemide--a powerful diuretic--daily.

All of which is by preface to my own Ozempic experience. I went on Ozempic last January (2023) and decided to go off it in December. I was on the 1ml dose for most of that time, and I took my weekly shot as part of my daily pharmacopeic intake. Incidentally I was shooting up in the arm and not in the belly as you mention, which apparently didn't have any adverse effects. In any event nobody told me different and I don't even know if that's what the instructions say: all I know is, Ozempic uses the same injector pens and disposable needles as Levemir, no doubt owing to the fact they're both Novo-Nordisk products.

During that time, I lost about another twelve pounds. That's it. And after six month of not being on Ozempic, I've regained about half that--but only half. I suspect that the reason is the mechanism by which the doctor explained to me--and there's articles on the web that confirm this--Ozempic causes weight loss: it slows down the rate at which your stomach digests food, meaning you fill up faster and stay full longer.

So, why did I go off it? Simple enough: I found it to be like a chemical form of lap-banding. To be clear, I am not lap-banded myself, but I know a couple of people who have undergone the procedure and they all say the same thing: lap-banding doesn't reduce your desire for food, it just keep you from ingesting more than a few ounces at a sitting. If you eat too much at one go, you experience uncomfortable sensations of fullness and in some cases it may cause reflux.

So instead of eating three squares a day, my lap-banded friends started eating a half-dozen or more smaller meals a day. After a while--as is pretty much universally the case with diets of all sorts (you mention this)--they weighed as much or more as when they'd started.

I experienced some of those same sensations, and I found it very unpleasant, the more so that food is one of the few sensual pleasures left to me in this life. As I like to say, I might not live to be a hundred if all I ate was dry toast and all I drank was plain water...but it sure would feel that way.

So I decided the game was not worth the candle, and thus I went off the drug. Since apparently these effects on your stomach are permanent, I surmise I've kept part of the weight off for that reason. But that is pure speculation on my part.

I make no recommendations and my experience is but a single data point. But I share it with you to give you some real-world experience with which to weigh what you read about this drug.