Understanding Tariffs: The Case FOR and AGAINST Tariffs

Although he apparently didn’t use the word “tariff,” Donald Trump has been publicly making comments that implied he supported tariffs as far back as the 1980s. When he ran for president the first time, he promised to put tariffs in place and did so on China, Mexico, Canada, and the EU among others.

The results of his tariffs seemed mixed, but Trump promised to try again in his second term, and he has. Like a lot of things Trump does, his tariff policy has been strategically ambiguous. His messaging varied enough that it was a little hard to definitively tell if he intended to put temporary tariffs on countries to get them to drop tariffs on the US, to create policy changes in other nations (both of which I think would be unambiguously good things), or whether he intended to put long-term tariffs on foreign goods in place to address the trade gap and raise revenue for the government.

It now appears to be the latter option, which has raised a lot of questions that are a bit difficult to answer because the United States hasn’t done more than dabble in tariffs since the 1930s when the arguments for free trade won out.

With that in mind, there are a lot of people who think they can tell you definitively what’s going to happen with these tariffs, but there are such big positive and negative impacts of tariffs that it’s hard to say for sure how they will shake out over time.

With that in mind, it’s worth going over both the case FOR and AGAINST wide-scale tariffs.

Since the conventional wisdom on the Right has been anti-tariff for quite a while, let’s start with the case AGAINST TARIFFS.

First of all, most conservatives have considered themselves to be “free traders” almost by default over the last few decades. Conservatives have posited that free trade increases the amount of prosperity in the United States and whether other countries put tariffs on American goods or we have a trade deficit doesn’t matter all that much.

For example, when I interviewed the late, great Milton Friedman back in 2012, he essentially said free trade allows us to get rid of inefficiencies in our workforce and that the money will ultimately get reinvested here:

John Hawkins: Let me ask you about this — what do you say to people who claim that free trade will eventually lead to high unemployment in the US as large numbers of jobs move to cheaper labor markets overseas?

Milton Friedman: Well, they only consider half of the problem. If you move jobs overseas, it creates income and dollars overseas. What do they do with that dollar income? Sooner or later it will be used to purchase US goods and that produces jobs in the United States.

In fact, all of the progress that the US has made over the last couple of centuries has come from unemployment. It has come from figuring out how to produce more goods with fewer workers, thereby releasing labor to be more productive in other areas. It has never come about through permanent unemployment, but temporary unemployment, in the process of shifting people from one area to another.

When the United States was formed in 1776, it took 19 people on the farm to produce enough food for 20 people. So most of the people had to spend their time and efforts on growing food. Today, it’s down to 1% or 2% to produce that food. Now just consider the vast amount of supposed unemployment that was produced by that. But there wasn’t really any unemployment produced. What happened was that people who had formerly been tied up working in agriculture were freed by technological developments and improvements to do something else. That enabled us to have a better standard of living and a more extensive range of products.

The same thing is happening around the world. China has been growing very rapidly in recent years. That’s because they shifted from a very inefficient method of agricultural production to something that comes close to the equivalent of private ownership of the land and agriculture. As a result, they’ve been able to produce a lot more with many fewer workers and that has released workers who have come into the cities and have been able to work in industry and other areas and China has been having a very rapid increase in income.

These arguments are frequently made in favor of free trade, but neither of them is bulletproof. One of the engines of economic growth is certainly improving the quality of jobs available to the workforce, but there are limits on how far that can go (remember coal miners being told to “learn to code”), and the idea that money we pay other countries almost has to be reinvested in the United States has always seemed like at least somewhat of a questionable assumption that may not be true tomorrow, even if it’s somewhat true today.

Another talking point we heard from conservatives opposed to George Bush’s tariffs on steel that were designed to protect the industry was that yes, it may protect those steel worker’s jobs, but the higher cost of steel will increase costs in other industries and will be likely to cost jobs in those industries.

That’s certainly a fair point.

You also hear many people claim the notorious (well, to economists) 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act didn’t cause the Depression but made it significantly longer and worse. However, to be fair, that is a dubious, unproven assumption. Personally, I tend to agree with Milton Friedman’s view that the Depression was caused by a massive number of bank failures and a dramatic contraction of the money supply in circulation, while Smoot-Hawley wasn’t a big factor.

From a political standpoint, tariffs can also be problematic because they make foreign goods more expensive and as we saw during the last election, Americans do not like paying more for things one bit. In addition, the reaction of the crypto and stock market to the tariffs has been very poor. There’s also a possibility we could see countries harm our economy with retaliatory tariffs instead of cutting deals because they may hope Republicans get creamed in 2026 and Trump has to give in. Whatever the case may be, if things get significantly more expensive and the stock market stays down by the time the next election rolls around, the Republican Party will almost certainly take a big beating at the ballot box.

Last but not least, the ultimate argument would probably be that the United States has embraced free trade for at least eight decades now and most people believe it’s one of the reasons we’re the most prosperous country in the world.

Now, what about the counterargument? What is the case FOR TARIFFS?

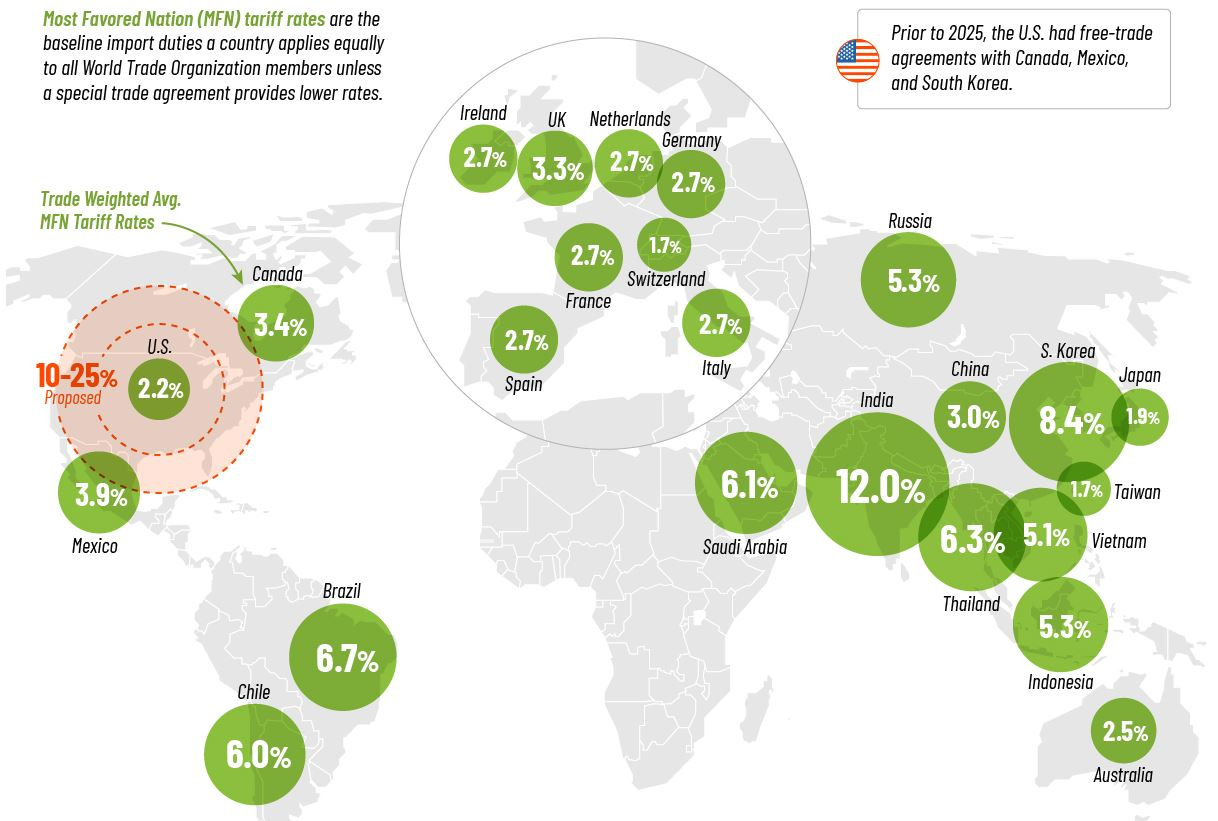

As a starting point, it would be that the United States heavily relied on tariffs from the early days of the country all the way into the 1930s. So, tariffs have a long rich history not just in the US, but in many countries across the world as you can see here:

Furthermore, many people would note that the United States has a unique advantage. We’re the largest market on planet Earth. So, we are THE PLACE people want to sell their products. So, what is going to happen if tariffs make products shipped into the United States from other places non-competitive? Those businesses will need to move HERE. In fact, there is at least some evidence this is happening. As the Trump administration has noted, the US has already secured a surprising amount of investment since Trump took office:

Thanks to President Trump’s leadership, the United States has already secured more than $3 trillion in private investments during his second term.

In addition, the tariffs will lead to people in our country buying more American goods, which will further spur the economy. Between that and the foreign companies moving here, there is a good argument to be made that it will create a lot of high-paying American jobs.

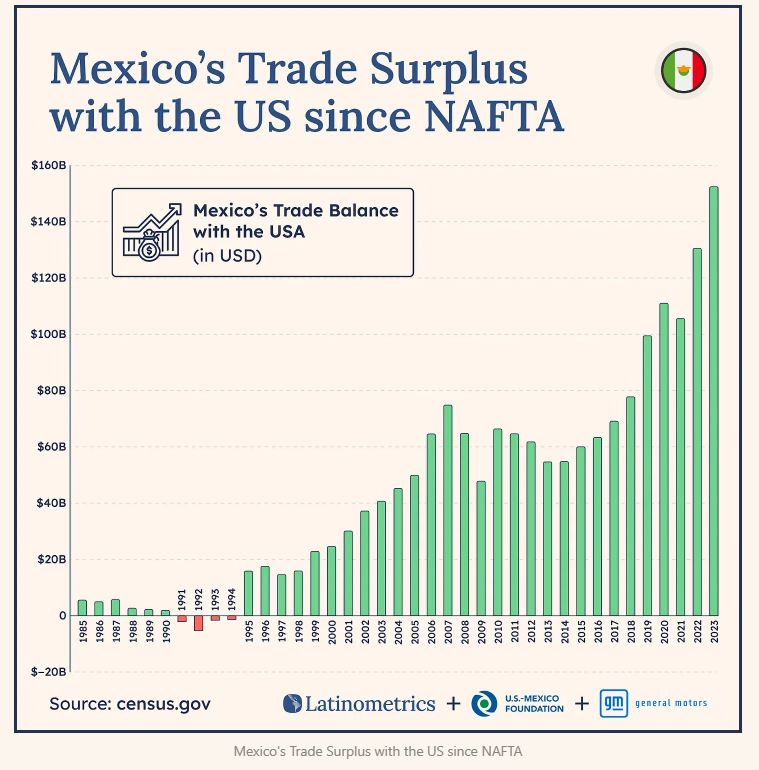

Furthermore, many people would counter the idea that free trade made America prosperous. For example, there’s a good case to be made that NAFTA was a terrible agreement for the United States and that none of the things free traders said would materialize as a result of it ever happened.

I worked on Congressman Duncan Hunter’s presidential campaign in 2008 and here’s what he had to say about that all the way back in 2006:

Duncan Hunter: Well, with NAFTA, Mexico also has a rebate system for their producers. So, if you want to operate tax-free, you go to Mexico. You create products and you ship them back to the US and you get your taxes rebated to you and you ship them back into the US.

So, and incidentally, on NAFTA, I led the debate against NAFTA on the Republican side in ’94. The proponents said, “Listen, we have a 3-billion-dollar trade surplus with Mexico. It’s one of the few countries in the world in which we have a trade surplus,” and here are their words, “Let’s build on that.” We passed NAFTA and the next year we went into a 15-billion-dollar trade deficit and we’ve never come close to coming out of it. So what they predicted didn’t happen. They also predicted that we would build a middle class in Mexico that would buy more washing machines and Cadillacs; that never happened. They also predicted that the illegal immigration problem would be solved; that never happened and they also predicted that the problem with massive drug trafficking into the US would be solved; that never happened.

Incidentally, he was spot-on about all of that. I wish we had run him instead of John McCain in 2008:

We also can’t forget that tariffs seem likely to raise a lot of tax revenue. So much so that the Trump administration has floated the idea of potentially no longer requiring people making under 150k to pay income taxes:

President Donald Trump has flirted with the idea of abolishing the IRS and creating a revenue stream from tariffs to offset major tax cuts. His latest pitch reportedly calls to end taxes for individuals earning less than $150,000 a year.

“I know what his goal is — no tax for anybody making under $150,000 a year,” Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick told CBS News. “That’s his goal. That’s what I’m working for.”

Lutnick later walked his assertion back adding that Trump would consider such a massive tax cut if he were able to balance the budget (a feat that hasn't been accomplished since 2001 under the Clinton administration, when the U.S. last experienced a fiscal year-end budget surplus).

At this point, is that feasible? It’s very difficult to say because we don’t know how much revenue the Trump tariffs will bring in and balancing the budget is genuinely a heavy lift. Even if we did, as you can see, it would be considerably easier to waive income tax for people making less than $96,900 than going all the way up to 150k, but of course, that would still be a politically revolutionary moment if it happened:

In other words, you can make a pretty good case for going either way. On the free trade side, it comes down to, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” On the pro-tariff side, the argument would probably be something more like, “It’s a lot more broke than it looks under the shiny exterior. We’re giving up an enormous amount of tax revenue and great jobs in return for not much when tariffs are an easy fix.”

Again, it’s genuinely too early to say which side is right and we may never know for sure because unless we have an awful lot of positive feedback on this policy by next year, the political pressure may get too strong to bear and Trump may have to back off on this policy and cut face-saving deals before we really find out if it works.

In the interim, it feels like Trump has earned the right to give this policy a go, so all we can do is cross our fingers, watch carefully, and see how it all plays out.

Good piece, thank you.

My view is that Milton Friedman was right in that free trade was the basis for America’s economic success as a country.

And in that regard, it was wildly successful as our per capita GDP has accelerated way past Europe’s over last 20 years or so when we used to see parity. What it did do is ship create millions of knowledge jobs and reduce certain jobs overseas where manufacturing costs were lower. Thus, it rewarded knowledge workers (where we excel) and harmed blue collar jobs (where our wages, taxes, and regulatory costs make us uncompetitive).

What we should have done at a national level is create Jack Kemp like free enterprise zones with reduced regulatory oversight and reduced taxes, to make those manufacturing jobs we lost more competitive for those not participating in the knowledge economy.

In the end, free trade would have likely worked better for more Americans if other countries took the same approach. For instance, Canada charges is what, 250% on dairy products and we’re at 2% or something like that? That obviously doesn’t work and isn’t fair. That being said, reciprocal tariffs would make more sense and would have the added political benefit of being fair. Putting tariffs on countries like Israel, after it agreed to drop all of its tariffs makes no sense.

So, while I am against tariffs, I’m willing to see if they’re being used as a tool to reduce tariffs against U.S. (which is a good idea) or a long term economic plan (which would likely be a terrible idea).