We’re Never as Smart as We Think We Are

The Sparrow Problem

In the late fifties, China was working very hard on improving its agriculture, but they were still having a problem growing enough food. Their tyrannical leader, Mao, studied the situation and thought he had found the problem.

It was the sparrows.

You see, the sparrows were cumulatively eating a lot of food. In fact, Mao had calculated that every dead sparrow would mean four more pounds of grain for the Chinese people. So, the Chinese government created a new law requiring the Chinese people to hunt, kill, and destroy every sparrow they could find. The campaign was very successful and hundreds of millions of sparrows were believed to have been killed.

So, did that lead to a massive abundance of food for the Chinese people as expected?

Not exactly.

Because, you see, sparrows don’t just eat grain and rice. They also eat insects. Without all those sparrows around to keep them in check, hordes of insects, particularly locusts, started devouring Chinese crops.

Estimates vary, but before it was all said and done, somewhere between 15-45 million Chinese people starved to death. Ironically, one of the keys to ending the famine turned out to be 250,000 sparrows the Chinese imported from the Soviet Union that helped get the locusts under control.

That may seem like a bizarre story that led to great suffering, but it’s actually just another variation on the same story of what has gone wrong with the human race all over the world in general, but here in America over the last two decades or so in particular.

Why? What do I mean by that?

Well, let’s start from the bottom up.

We humans have this tendency to believe that we’re brilliant and scientifically advanced. We think we’re smarter than our ancestors, we have it all figured out and we understand all of what’s going on.

In some ways, this is true, but in most ways, it’s not and in a few ways, we’re getting progressively dumber by the second.

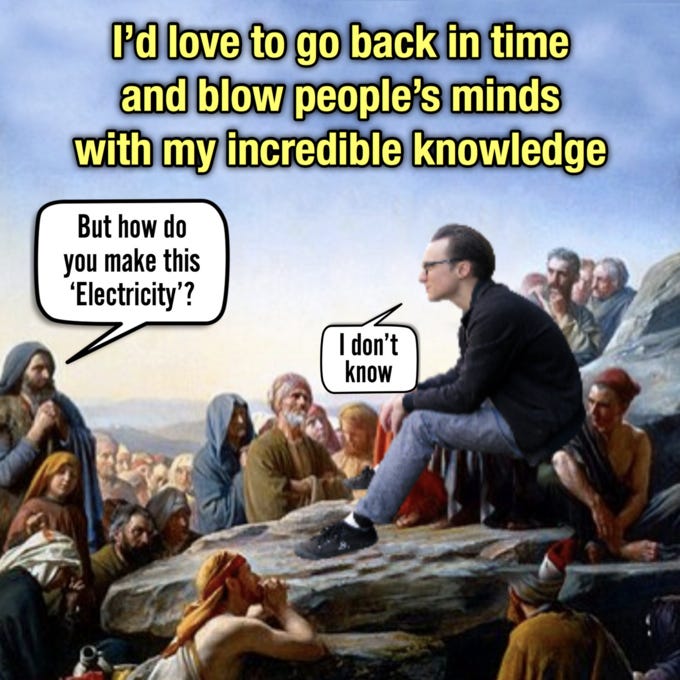

Imagine going back in time to the most powerful Egyptian Pharaohs, Caesar, or the Spartans and telling them you were from the future. They might look at your clothes and your nifty cell phone and be fascinated by a few of your tales of the future. But then, imagine what would happen when they started trying to get practical information out of you:

Not only do we not know how to create most of the things we use on a daily basis, every year there are new things we don’t know of being invented. Of course, this is hotly debated, but the last time a single brilliant human being supposedly had a strong working knowledge of ALL the current sciences was in the early 1800s. Meanwhile today, by some accounts, so many experiments and trials are being done that our medical knowledge is doubling every 73 days. In other words, it’s difficult to truly be an expert in even one field, which only represents a teeny, tiny fraction of our own knowledge. Meanwhile, even the smartest of us are ignorant of most things.

On top of that, you have to remember that we still don’t fully understand some subjects that we’ve thought about and studied for thousands of years, like what the ideal diet is for a particular human being or how exactly our bodies most optimally build muscle. How does the placebo effect actually work? Where does our consciousness come from? Why do we dream?

Don’t get me wrong, we know a lot about those subjects, but there’s a great deal that even the foremost experts in the fields don’t understand. There are many such subjects like that.

Furthermore, all that’s just the tip of the complexity iceberg. Keep in mind that your humble author who is writing this column for you right now made an awful lot of his money in a career that didn’t exist when he was born (blogging). He is writing this on a device that wasn’t widely available when he was born (a computer) and is preparing to call a friend on a cell phone (a device that didn’t exist when he was born) before checking his X account (which didn’t exist when he was born). He is also posting this column to Substack, which has been around for 7 years. In other words, we’re in an ever-shifting, ever-changing, increasingly complex world.

In other words, we’re all walking around thinking we understand the world around us, going, “If only we could kill those damn sparrows, everything would be great,” when we really know much less about the world than we believe we do.

So, how can we fix that – well, best as it can be fixed?

It starts by recognizing that we don’t know as much as we think we do and changing the way we approach the world both as individuals and as a society.

1) Copy what works: Despite all our complexity, we human beings tend to go down the same paths over and over again. The terminology, styles, and technology may change, but human nature doesn’t change that much.

If you read a lot of history, you will see a lot of patterns. Follow the successful people, the successful civilizations, the things that have worked in your civilization in the past. What worked in the past is never a perfect roadmap to what will work in the future, but it’s infinitely more effective than just trying whatever sounds good or what the unsuccessful masses think will work.

Copying Usain Bolt’s training may not make me a fast runner, but it’s a lot more likely to work than asking my cousin how to get faster or just guessing what might work.

2) Think in terms of probabilities, not absolutes: Nothing is guaranteed, but some things are more likely than others. Try to understand the possibilities of success and failure & make sure the juice is worth the squeeze. In other words, test, reassess and be adaptable.

3) Experiment: One of the many things that revealed the genius of the Founding Fathers was their emphasis on states' rights. As each state tries something, it can be evaluated by other states to see if it’s worth copying.

The same goes for individuals. In a nation with 330 million people, people are living in almost every imaginable way. Which ones produce success? Happiness? Who’s getting ahead and who’s falling behind? Who’s winning and who’s losing?

Why would you look at people who objectively seem to be unhappy, miserable, and failing, and then copy that way of living? Yet, people knowingly do exactly that every day of the week in America and unsurprisingly end up just as miserable, unhappy, and unsuccessful as the people they’re copying. Then, it’s like, “Duh! What else did you expect?”

4) Avoid One-size-fits-all centralization as a solution: The system of governance that works so well in America didn’t work when we tried to impose it in Afghanistan. A drug that might save your life might also kill your neighbor. The same guy who would make a world-class offensive tackle would be a terrible marathon runner. There is ALWAYS an exception to the rule and often, there are legions of exceptions to the rule, lots of unexpected consequences, and trade-offs that no one expects.

There is no “legion of experts” that can tell you exactly what to do with your life or make decisions for 330 million people that are better than each of those people would make individually.

The reason why this is such a critical mistake is that all across our society, from the individual level all the way up to the government level, there are people out there trying to adopt or push a one-size-fits-all solution on everyone. Someone doesn’t want to eat meat, so everyone needs to be a vegetarian. Someone is scared of guns, so they all need to be illegal. Someone has decided, usually based on lazy, specious thinking, that some “ism” is responsible for their failure, so they decide society has a big problem with that which needs to be addressed instead of fixing their own life.

They don’t think about the trade-offs or the potential consequences, they just believe that they have the right idea, so everyone needs to be made to do it. This is a fundamental conceit of far too many human beings. They have decided that their idea is right for whatever reason, so they don’t see the need to bother with all those other pesky steps.

This is where Mao truly went wrong. He was too sure of himself. He didn’t experiment. He didn’t test. Instead, he went forward with a one size fits all solution and killed millions of people. Hopefully, no one reading this will ever make a mistake that big, but we can all make the same kind of mistake when we think we know more than we do, when we get lazy, when we get too full of ourselves.

Unsuccessful people and nations often just do whatever sounds good and hope it works out. They’re always so sure about their own personal “sparrows” that they don’t even see a need to test, debate, or prove their case. Then, when they almost inevitably fail because they didn’t know as much as they thought they did, there’s always an excuse. Meanwhile, the truth is very different:

At the end of the day, none of us is ever as knowledgeable or smart as we think we are. That’s why all of us should be humble, accept that there’s a lot that we don’t know, learn from successful people and strategies, test our theories, and change course when needed.

Since I don't have to take part in a day-to-day endeavor in the business world, thank God I don't have to know more than I already do to function in this ever-changing world. And thank you, John Hawkins, that I have access to such invigorating think-pieces on Substack to keep my mind active and alert--and to share these posts to others.

Nice. Also... there really is nothing new under the sun. It has all been there all along. We may discover things previously unknown by us, but it was always part of creation. We aren't the creators, just the finders.