What Americans Can Learn from Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany

WWI was initially triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, by a Serb nationalist. From there, a disastrous series of alliances dragged a number of other nations with simmering rivalries into the war.

Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The Russians sided with Serbia. Germany, which was an ally of Austria-Hungary, declared war on the Russians. The Germans also feared being encircled by France, so they invaded Belgium to get to France. The Brits were allies of Belgium, which then led to the Brits getting involved. Later on, German subs kept sinking American ships, and, fearing American involvement, pre-emptively tried to get Mexico to attack the US. This led to America getting involved and Germany's defeat.

Afterwards, on the upside for them, Germany was not decimated during the war in the same way France or Belgium had been. However, Germany still had three serious problems.

The first was that they had essentially financed the war with the printing press, and now the bill was coming due.

Meanwhile, they were less able than ever to pay it because they lost a large amount of territory and were hit with massive demands for reparations from Britain, Belgium, and most of all, France. Incidentally, “massive” comes out to about 500 billion dollars in today’s money, which is an extraordinary sum.

Last but not least, the French quite understandably despised the Germans and viewed reparations as a way to keep their boot on Germany’s neck. So, they simply didn’t care how bad things got in Germany.

The Germans were faced with two economic choices. They could deal with an enormous amount of short-term pain caused by tightening their belts to pay for things, or they could opt for delayed pain caused by cranking up the printing presses to pay bills today, while watching the population be crushed by inflation tomorrow.

The Germans went the same way that nations with fiat currency always seem to go. The same way America went during COVID, when we printed roughly 20% of our money supply to get us over the hump caused by the government-ordered shutdowns and the virus. The results of that German choice were catastrophic, and we’re going to discuss some of them with excerpts from the book, When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany.

First of all, this quote should give you a sense of how bad the inflation got in Germany after the war:

In October 1923, it was noted in the British Embassy in Berlin that the number of marks to the pound equalled the number of yards to the sun. Dr Schacht, Germany’s National Currency Commissioner, explained that at the end of the Great War, one could in theory have bought 500,000,000,000 eggs for the same price as that for which, five years later, only a single egg was procurable.

Once you get to that point, cash isn’t quite useless, but it’s close, so people started bartering and spending their money as fast as possible because they couldn’t be sure if it would be worth as much next week, or maybe even later THAT DAY, as it was the moment it got into their hands:

The private tradesman already refuses to sell his precious wares for money and demands something of real value in exchange. The wife of a doctor whom I know recently exchanged her beautiful piano for a sack of wheat flour. I, too, have exchanged my husband’s gold watch for four sacks of potatoes, which will at all events carry us through the winter.

Foreigners also got in on the action:

The bread and rail subsidies, financed by inflation, combined with the rent restriction, enabled the foreigner to buy German goods well below world prices and, if he lived in or visited Germany, to travel, eat, and occupy houses at ridiculously cheap rates. ‘A gradual process of buying up and carrying off Germany’s movable capital, secondhand furniture, pianos, etc., is taking place at the expense of Germany as a whole.’ Foreigners were also buying up real property and interests in factories and all kinds of businesses.

Of course, it took some people a while to figure out what was going on, and they kept pursuing the ever more worthless cash:

The last valuables of countless houses flowed onto the market, no one warning their owners not to part with goods whose intrinsic value remained unimpaired. The Viennese [commented Frau Eisenmenger], handed a large bundle of kronen, still thinks he has grown richer, without taking into account the enormous rise in prices resulting from the Zurich quotations, which come as a fresh surprise to him every day.

In this environment, anybody doing better than most other people becomes despised by people struggling to make it:

Jealousy and envy flourish in this atmosphere, and if one has procured some harmless article of food, one is careful to conceal the fact from one’s fellow men. Hunger reigns inexorably and selects its dumb and uncomplaining victims above all from the middle classes.

Additionally, most people didn’t really understand what was going on. They just understood they were suffering and were looking for scapegoats:

‘By the end of the year,’ said Erna von Pustau, my allowance and all the money I earned were not worth one cup of coffee. You could go to the baker in the morning and buy two rolls for 20 marks but go there in the afternoon and the same two rolls were 25 marks. The baker didn’t know how it happened … His customers didn’t know … It had somehow to do with the dollar, somehow to do with the stock exchange - and somehow, maybe, to do with the Jews.’

Crime exploded as the whole population was willing to do anything to survive:

Petty crime, the crime of desperation, was flourishing. Pilfering had, of course, been rife since the war, but now it began to occur on a larger, commercial scale. Metal plaques on national monuments had to be removed for safekeeping. The brass bell plates were stolen from the front doors of the British Embassy in Berlin, part of a systematic campaign unpreventable by the police even in the Wilhelmstrasse and Unter den Linden. That members and families of the British Army of the Rhine suffered severely from burglaries probably reflected the fact, not that thieves had particular animus against the forces of occupation, but that these days foreigners were so much more robbable than anyone else. Over most of Germany, the lead was beginning to disappear overnight from roofs. Petrol was syphoned from the tanks of motor cars. Barter was already a usual form of exchange, but now commodities such as brass and fuel were [as well].

As the nation’s currency became ever more useless, other people created their own currencies:

Communities printed their own money, based on goods, on a certain amount of potatoes, or rye, for instance. Shoe factories paid their workers in bonds for shoes, which they could exchange at the bakery for bread or the meat market for meat.

Eventually, it got to the point where people were pushing around wheelbarrows full of cash, which was not just inconvenient, but it made paying for things a very slow process because massive amounts of cash had to be counted out even for relatively small purchases. Also, as you’d expect, this led to German society becoming increasingly non-functional:

In Berlin, the tramway system ceased to run through a lack of means. In villages where no municipal or other emergency currency was available, a sudden drop in the value of the mark would leave the community with too little money to carry on at all, and in isolated villages, this would occur without any warning. The sight of shoppers with baskets full of banknotes was now common in every town. ‘You could see mail carriers in the streets with sacks on their backs or pushing baby carriages before them, loaded with paper money that would be devalued the next day,’ said Erna von Pustau. ‘Life was madness, nightmare, desperation, chaos.’

The lack of money also started to lead to food shortages because farmers quite correctly understood that their food was valuable, while paper currency was nearly useless:

The new danger was that when the peasants finally refused to deliver produce to the towns, the towns would go and fetch it. It had happened in Austria during the blockade. It had happened in the Ruhr and the Rhineland under the provocation of French militarism and enforced idleness. Now there were reports from Saxony - unoccupied Germany - that bands of several hundred townspeople at a time had taken to riding out into the countryside on bicycles to confiscate what they needed. The towns were starving. The countryside had had a bumper harvest, but there it remained because of the farmers’ steadfast refusal to take paper for it at any price.

It should be no surprise that extremists like Hitler, the communists, and local tinpot dictator-wannabes were able to gain steam under those circumstances. It’s similarly not a surprise that rampant anti-Semitism spread, especially when so many Germans were looking for scapegoats because they were reluctant to admit that their much admired military had simply lost the war, and their government’s choice to print so much money was ruining them.

Eventually, the Germans created a new currency that they didn’t rapidly expand, which stabilized prices. However, paradoxically, being more financially responsible led to a period of mass unemployment, a shortage of cash, and a tremendous amount of suffering as the economy adjusted to the situation. Over time, Germany regained its economic footing and turned to Hitler, in part, to repay the humiliation they suffered during that period, much of which they correctly blamed on the French.

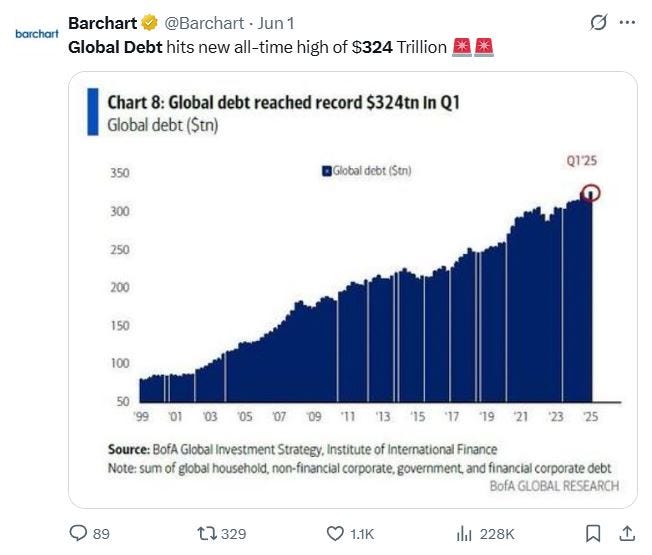

Americans should pay a lot of attention to this, not just because we’re also headed toward hyperinflation down the line, but because much of the rest of the planet is also:

It’s entirely possible the US might have already been unable to service our debt, except for the fact that almost the entire globe is playing the same game we are with their money. The upside of that is that we may look like the best of a lot of bad options to many people, but the downside is that fiat currency is a confidence game.

We can’t back our currency. Neither can anyone else. If people lose faith in those pieces of paper, which in many cases are backed by assets worth far less than the value of the money, things can get very dicey, very fast, and the first solution to that problem most governments pursue is printing more increasingly worthless pieces of paper.

So, could what happened in Weimar Germany also happen in the United States one day? Absolutely.

In fact, the odds are something like this will happen in the lifetimes of most of the people reading this, although it’s impossible to say when. However, when it does happen, if you look back at history and see what other people did in these situations, it may at least give you some clues as to how you can navigate that nightmare better than most of your fellow citizens.

Thank you, for posting. People need to understand the dangers we face based on the reckless vote buying, er “spending,” of both parties. This is a helpful start, especially since so few people care to learn history.

A glimpse at our future in the U.S. unless, somehow, the tide is turned by policies that tighten the belts of spending by administrations whose platforms are geared toward power and control by the elites. Your treatment of this issue is welcome and sorely needed to awaken a citizenry to the seriousness of how dire the situation could become. Sharing . . .